USA

Beating a Path Through the Heart of Northern Maryland

by Randy Mink

Being a hiking enthusiast, history hound and fan of quaint little towns, I found lots to like during my recent trip to north-central Maryland, a part of the state that seems light years away from the Baltimore-Washington, D.C. metro area.

When many of us think of Maryland, we think Baltimore, Annapolis and other cities on the Chesapeake Bay. But I was traveling through the farmscapes and forested mountains to the west—specifically Frederick and Washington counties. Bordered by Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia, the region is a tantalizing blend of Appalachian and sophistication.

I based myself in Frederick and from there made easy excursions through the tranquil green countryside that starts right outside the city limits. Though Frederick is Maryland’s second-largest city (population 80,000), the friendly vibe and sense of community give it a small-town feel.

Exploring Historic Frederick

Downtown Frederick boasts a 50-square-block historic area loaded with 19th century buildings, including brick row houses and churches sporting stately spires. Extremely walkable, the district abounds with specialty shops and restaurants. Its crown jewel is Carroll Creek Park, whose landscaped promenades invite strolling on both sides of the creek. Clustered at one end are several breweries and a distillery. A hub for concerts and other special events, the linear park claims the largest free water garden in the world, featuring picture-perfect lily pads and exotic vegetation from the Amazon jungles.

Downtown’s National Museum of Civil War Medicine, a must-see, provides fascinating insights into early medical practices and the human suffering caused by the 1861-1865 war that tore the country apart. For one thing, you learn that two-thirds of the 700,000-some soldier deaths resulted from diseases spread by unsanitary conditions in crowded camps, not bullets and bayonets. Many succumbed to dysentery.

Major advances developed during the war—like the design of prosthetic limbs and a triage system for treating the wounded—changed medicine and battlefield evacuation techniques forever. Amputations were the most common surgery performed in field hospitals, almost all of them done with the patient under some form of anesthesia, mainly chloroform or ether inhaled through a cloth.

Thousands of wounded Civil War soldiers were treated in homes, barns, churches and places of business in Frederick and other towns in the region. The stories of soldiers, surgeons and civilians come to life on the museum’s “One Vast Hospital Walking Tour.”

Antietam: Carnage in the Cornfields

Many of those needing care were wounded at Antietam Creek, the site of an infamous battle. Antietam National Battlefield memorializes the valiant men who participated in the bloodiest single-day conflict in American history (September 17, 1862). Of the nearly 100,000 Union and Confederate Army soldiers fighting in the farmlands near Sharpsburg, about 23,000 were killed, wounded or missing.

As a Massachusetts infantryman wrote to his father: “The slaughter was more awful than anything I ever read about….there is no place where you can stand and not see the field black with dead bodies as far as the eye can reach.”

Antietam, one of America’s most beautiful and best preserved battlefields, today is peaceful, almost idyllic. The National Park Service site contains dozens of stone monuments—many crowned by rifle-toting or sword-wielding soldiers—and interpretive panels alongside a self-guiding tour route threading fields planted with corn, soybeans and wheat. One monument honors Clara Barton, “Angel of the Battlefield,” who brought bandages, lanterns and food to field hospitals and in 1881 founded the American Red Cross. Antietam’s newly renovated visitor center offers ranger talks, exhibits and a movie about the epic 12-hour battle.

On a happier note, my next stop was Bonnie’s at the Red Byrd, a roadside diner that’s been dishing out home cooking since 1958. At this Keedysville landmark decorated with cardinal knickknacks, I ordered the fried country ham sandwich platter, though the homemade BBQ pork and Wednesday specials (all-you-can-eat fried chicken and “slippery chicken” pot pie) were tempting. I saved room for chocolate meringue pie.

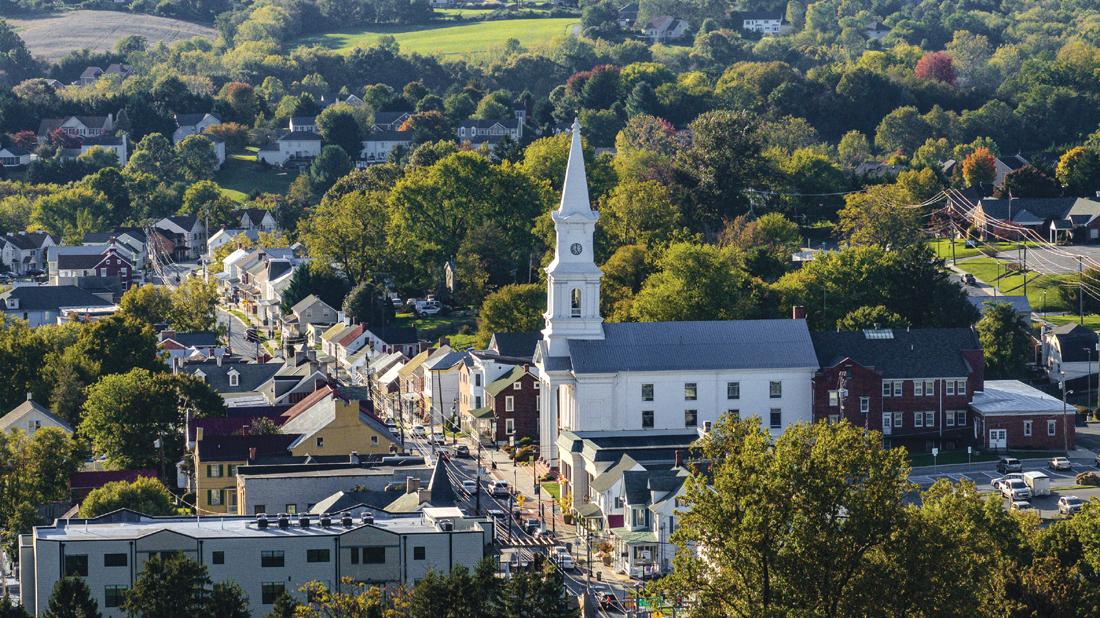

Main Street in Boonsboro

On the way to Boonsboro, I stopped at Crystal Grottoes Caverns for a cool 45-minute tour of Maryland’s only show cave. Then I spent an hour or so exploring Boonsboro’s Main Street with a walking tour brochure in hand. Established in 1792, the town thrived during the mid-1800s when the National Road, the nation’s first federally funded highway, brought prosperity. Now U.S. Route 40 and a Maryland Scenic Byway, the National Road, once busy with horse-drawn wagons and stagecoaches, crossed six states between Baltimore and St. Louis. The new National Road Museum is set to open soon on Main Street, joining other points of interest on the historic roadway’s path through town.

Boonsboro’s current claim to fame revolves around a famous resident, best-selling romance novelist Nora Roberts. On Main Street, she and her husband own a bookstore, a gift shop featuring the works of local artists and Inn BoonsBoro, an eight-room, literary-themed boutique property that occupies a former hotel popular during National Road boom years.

History and Hiking

Not far from Boonsboro, more Civil War history surfaces at South Mountain State Battlefield, which stretches between Washington Monument State Park (home to the first monument to honor George Washington) and Gathland State Park, near Burkittsville. The castle-like War Correspondents Memorial Arch at Gathland, dedicated in 1896, is inscribed with names of journalists killed in war. Museums across the road chronicle the Battle of South Mountain (waged three days before Antietam) and the life of noted Civil War correspondent George Alfred Townsend. Located in the northern Blue Ridge range, South Mountain claims a portion of the famed Appalachian National Scenic Trail, the 2,180-mile footpath that traverses the Eastern United States from Maine to Georgia.

Hiking opportunities also await on the towpath of C&O Canal National Historical Park, whose scenic hiking/biking trails hug the Potomac River for 184 miles from Cumberland, Maryland to Georgetown in D.C. One day I drove a segment of the C&O Canal Scenic Byway, getting off at two places for hikes to locks, lockhouses and aqueducts that once served boat traffic on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. For lunch, I stopped in the historic canal town of Brunswick and rewarded myself with a scrumptious turkey, cheese and cranberry panini in a former church turned cafe, Beans in the Belfry.

Catoctin Mountain Park, near Thurmont and just south of the Pennsylvania border, provided my favorite hikes in northern Maryland. Panoramic lookout points have to be reached on foot, as there are no roadside overlooks for motorists.

Driving through the park under leafy canopies, I passed a road posted with a “Do Not Enter – Restricted Area” sign and noticed a “No Photography” icon as well as a park police car. Having read some travel guidebooks in advance, I knew the “secret” road led to Camp David, the country retreat of U.S. presidents since the days of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The park’s visitor center carries two books on Camp David, but park personnel, understandably, are mum when the subject comes up.

Catoctin Mountain Park, a National Park Service unit, adjoins Cunningham Falls State Park, where one trail leads to Catoctin Furnace Village. A fascinating historical attraction dating from the early days of the Industrial Revolution, the village comprises ruins of the old iron-smelting furnace and ironmaster’s house, plus the Museum of the Ironworker and workers’ cottages that now are mostly private residences. The African American Cemetery Trail pays homage to the slaves who toiled in the furnace under hot, dirty conditions. The restored 1820 Forgeman’s House, furnished with antiques, offers overnight accommodations.