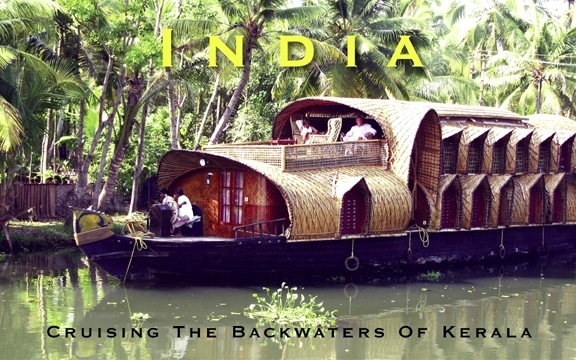

India

Cruising The Backwaters Of Kerala

by Margaret Deefholts

My son Glenn looks incredulous. He whispers: “Rs.300 for an eight hour cruise? That’s less than CA$8.00. Is the boat safe?” I nod and whisper back. “It’s not a luxury boat – but yes, it’s perfectly safe.”

Riyas Ahammed, who heads up Southern Backwaters company, is writing up our tickets. He hands them to me with a smile. “Hurry,” he urges. “The boat is leaving soon.”

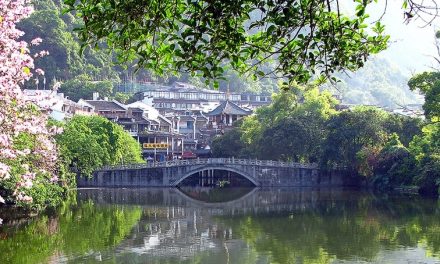

We are in the small town of Kollam on the west coast of India, and are all set to sail through the fabled Kerala backwaters—an intricate network of waterways extending from Kollam all the way to the port city of Kochi (Cochin). This day trip will take us half-way up the coast as far as Alleppey. Scrambling our way past souvenir stalls and locals waiting at a bus stop, we board our motor boat. “Not bad,” says Glenn as we settle into our seats on the covered upper deck. He fans himself with Southern Backwaters’ publicity pamphlet. “Sticky morning though.”

The upper deck rapidly fills up. The double-decker vessel seats 80 people, and most of them are foreigners: young backpackers, German, Italian and Scandinavian tourists, several Brits and Aussies. We seem to be the only Canadians.

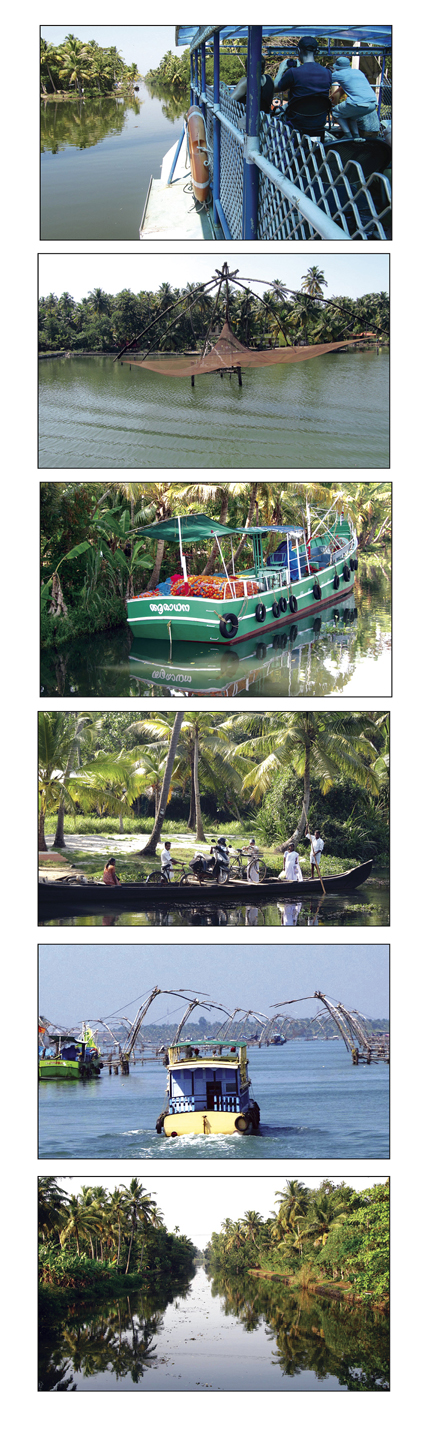

The engine roars into life and as we pull away to midstream, it settles into a steady growl. A light, breeze ruffles my hair, and Glenn exchanges his “fan” for binoculars. The waterway, bordered by dense tropical vegetation, is broad at first but, as I recall from an earlier trip on a similar boat, we soon veer off into narrow winding inlets. The view is soothing: waves stippled by sunlight, palm-fringed shores, and fishing nets slung from cantilevered masts which rear like pterodactyl skeletons against a steel-blue sky.

Sheltered within coconut palm groves, little village settlements are alive with activity: women slap their laundry on stones at the water’s edge and men cycle along narrow winding roads with baskets of bananas perched on their back-carriers. Naked urchins splash in the shallows, bobbing up and down, waving and shouting, “Hullo! Do you have pens? Chocolate?” Fishing nets are spread out to dry along the foreshore, and small whitewashed churches gleam in the sun. We chug past elaborate rattan houseboats, where passengers snootily deign to acknowledge us as they loll on their decks sipping shandies or iced coconut shakes.

Although the scenery along the backwaters is breathtaking, this part of Kerala’s coast is more than just a tourist tropical paradise. The canals, play an intrinsic part in the lives of those who live along its banks serving as transport for both people and goods. We pass a prim sari-clad matron sitting on a wooden bench in a dug-out canoe, looking for all the world like a stately maharani. Crowded municipal ferries putter self-importantly past us. Other barges, rusty old derelicts, carry cattle, bulging jute gunny sacks and baskets of coconuts. Fishermen, bare-bodied except for lungis (cotton loin-cloths) knotted around their waists, beam and wave. One of them hoists his prize catch—a large fish, still wriggling, its fins flashing silver in the sunlight. We clap and give him a thumbs up.

The boat pulls up to a jetty and we dismount for lunch. The restaurant is a large airy room with checked purple tablecloths and a simple buffet: fat-grained boiled white rice, three types of curried vegetables and a tray of bananas for dessert. All you can eat for just a little more than a dollar. Later we stop alongside the bank, for a tea break. Fifty cents buys sweet milky Indian chai and a selection of snacks: aloo bondas (deep-fried spicy potatoes wrapped in chick-pea flour), cones of roasted peanuts or coconut based sweetmeats.

As the warm, lazy hours slip by, we cruise along channels where green reflections of palm fronds and creepers tremble the waters. Water hyacinths lie like thick carpets on the canal’s surface—dense enough to choke the channels in some spots. We slow down to a wary putter. At a village jetty, bright yellow boats unload shimmering loads of fish, and around a bend, a festive procession, accompanied by a drum and flute, heads along an embankment.

By late afternoon, the scenery changes to broad paddy fields stretching to the horizon. Along a beaten-earth track edging the water school kids cycle homewards, and farmers carrying sheaves of hay return to their villages. Cooking fires begin to flicker like fireflies between the trees. The evening sunlight lays a mellow glow over everything and dusk falls gently on the tranquil waters. Alleppey’s jetty looms and we disembark. Reluctantly.