- Cuenca

- Cuenca

- Cuenca

- Cuenca

- Toledo

- Toledo

- Toledo

- Toledo

Spain

Tale of Two Spanish Cities – Medieval splendor dazzles visitors to a pair of charmers in the Castilla-La Mancha region of central Spain

Randy Mink

Hitting the Heights in Cuenca

With ancient buildings stacked on a steep promontory where two river gorges meet, Cuenca projects a dramatic profile, one different from any other city in Spain. Because it’s not on the traditional tour circuit, this medieval gem 105 miles southeast of Madrid, is off the radar of most North American travelers, a fact that adds to its beguiling appeal.

In Cuenca it’s all about the heights. Think vertical. Looking up or gazing down, you’ll find yourself constantly taking in the views. Traipsing around narrow streets and passageways, you’ll encounter one vantage point after another that provides a fresh new slant on the cliff-clinging houses.

Those afraid of heights get nervous crossing San Pablo footbridge, a wooden walkway that spans the Huecar River 200 feet below. It’s a major attraction in itself, an Instagrammable spot for sure. If you’re staying at Parador de Cuenca, as our group was, the bridge is the most direct way of getting to the atmospheric Ciudad Alta, or Old City. We crossed it several times a day. (Page 79 has my report on Parador de Cuenca, a monastery-turned-hotel.)

From the bridge you have fine views of Cuenca’s most emblematic attraction—the Hanging Houses, or Casas Colgadas. The wooden balconies of this trio of 14th century dwellings jut out over a sheer cliff. Appearing to defy gravity, the buildings seem about to topple off their perch and into the abyss. You can stand on one of the balconies if you visit the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art or gourmet restaurant Casas Colgadas Jesus Segura, tenants of the Hanging Houses.

In medieval times, why did builders push to the precipice? The answer: real estate was scarce and every foot counted. Because land was at a premium, some houses were built eight to 12 stories high. These “skyscrapers,” many of them today painted in bright colors, were among the tallest buildings in Europe until the 20th century.

Cuenca does not have a long checklist of must-see sights, which suits me just fine. I’m happy just wandering and getting lost in the cobbled lanes, soaking up the history that crosses my path—and taking picture after picture. The refreshing lack of tourist hordes makes it even more delightful.

The heart of this UNESCO World Heritage city is Plaza Mayor, which spreads in a linear fashion from the Cathedral, passing through the arch of the town hall. Outdoor cafes lend a lively air, and the red tram departs from the square for tours.

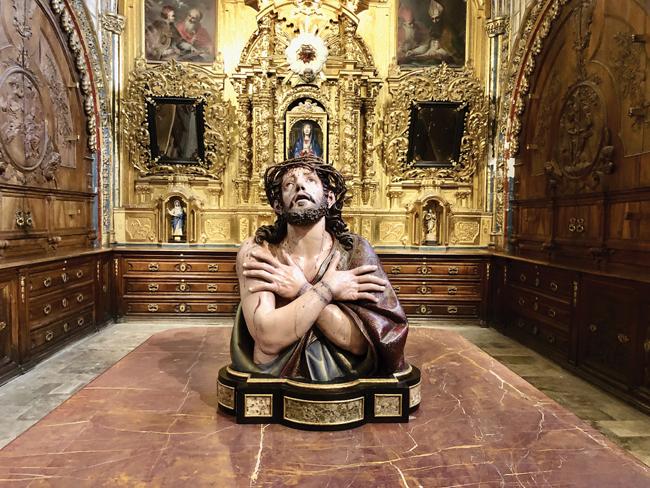

While Spain has better known churches, Cuenca’s cathedral is truly impressive. Largely built between 1156 and 1256, it was the first Gothic church on the Iberian peninsula. Statuary, paintings, expanses of marble and lavishly adorned chapels reflected the city’s wealth in medieval days. The two pipe organs date from the 18th century. Our group heard their melodious sounds while seated in the ornately carved wooden choir stalls during an evening concert.

If staying in Cuenca overnight, make sure to walk the footbridge after dark and cast your eyes on the Old City’s rock face, floodlit in all its glory. The magical vision lingers long after a visit to this intriguing city off the beaten path.

www.spain.info/en/destination/cuenca/

Toledo: A Perennial Crowd-Pleaser

I could spend hours roaming through the tangle of cobbled pathways that thread the historic core of Toledo, one of the best places in all of Europe for getting lost in a medieval dreamscape. Loaded with Old World magic, Toledo projects the very essence of Spain and was once its capital.

On a recent visit to this fascinating city rich in Christian, Jewish and Muslim heritage, I never tired of probing the labyrinth’s nooks and crannies while popping into souvenir stores, touring museums, and traipsing through an ancient synagogue, the world’s fourth largest cathedral and a former mosque built during the Moorish occupation.

Like the Old City district of Cuenca, another charmer in Spain’s Castilla-La Mancha region (see opposite page), Toledo’s extensive medieval quarter sprawls across a hilltop bounded by the original city walls and surrounded by a river below.

Located 55 miles southwest of Madrid, Toledo overflows with tourists—attracting a million of them every year—and its pedestrian alleyways abound with gift shops. I’m not ashamed to say I loved shopping for refrigerator magnets and other tchotchkes in Toledo, but I also liked stepping away from the commercialism to explore back lanes accented with wrought-iron balconies, grillwork windows and massive, centuries-old wooden doors. Some of Toledo’s narrow streets do allow cars, however, so be prepared to stand flat against the buildings to spare your feet from being run over by drivers barreling up and down the inclines.

Long known for its quality cutlery, Toledo has many sword stores and calls itself the Sword Capital of the World. At the Zamorano sword factory, where we watched craftsmen at work, one fellow traveler shipped home two swords, fitting reminders of this fortified city that harks back to the days of knights in shining armor. Since the Middle Ages, Toledo has been known for its steel craftsmanship. Stores offer a fine selection of knives, letter openers and scissors as well as swords, plus knight figurines in all sizes.

Candy is always a good thing to bring home, and I stocked up on marzipan at Santo Tome’s flagship store. The seventh-generation family company has been making its famous almond paste confection since 1856. For gift-giving, I bought wrapped boxes of six-inch marzipan bars inscribed “T-O-L-E-D-O,” but my own bag of marzipan pieces was gobbled up before I got to the Madrid airport.

In between shopping and wandering footloose in the dense medieval mazes, I checked off a few places from my must-see list, including the El Greco Museum. Toledo is synonymous with the Greek-born painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, or “The Greek.” He moved to Spain in 1571 from the island of Crete and today is venerated as one of the country’s old masters, along with Goya and Velazquez.

El Greco’s religious canvases, distinguished by bold colors and elongated figures in voluminous robes, can be seen in the museum bearing his name and in Toledo churches and other museums.

The El Greco Museum resides next door to the 14th century El Transito Synagogue with its Arabic-influenced interior decoration, coffered ceiling and museum of Sephardic Jewish culture. The park across the street has a memorial to El Greco and a terrace affording panoramic views of the city, truly one of the most captivating places in all of Spain.