Indonesia

Tana Toraja, Sulawesi, Indonesia: A Defining Experience

Article and photography by Steve Gillick

Sulawesi is a captivating destination for travelers looking to connect and interact in a personal, meaningful way. During our five day visit, we attended funeral ceremonies, visited cave, cliff and tree graves, met the fascinating Tau tau, trekked to remote villages and interacted with the locals selling their wares in the markets, planting the rice fields and doing household chores in and around their homes.

Our journey to Tana Toraja, “the land of the people of the uplands”, was motivated by an overall desire to gain insight into other cultures, inspired, no doubt, by my Grade 11 History Teacher who had us read portions of Sir James George Frazer’s classic study of mythology and religion, The Golden Bough.

But there was also a totally unexpected mystical intervention, when, on a flight to Irian Jaya (now Papua), our plane made a brief stop in Makassar, the capital of Sulawesi. At that time the airport terminal was designed to evoke the image of ‘Tongkonan’, the traditional, peak-roofed houses of the Torajan people. I was totally amazed and vowed that I would return one day. And I did!

Several years later, after a few days of discovery in Bali, we took the 75-minute flight from Denpassar to Makassar, where we met our guide for the seven hour (310 km) journey to Tana Toraja. Today there are one-hour flights from Makassar (a.k.a Ujung Pandang) to Palopo Bua Airport and then a two-hour drive to Rantepao, so the choice of transportation just depends on time, budget and curiosity.

We drove up the coast, making frequent stops to photograph landscapes of mountains and villages, scenes of small fishing boats and roadside stalls selling everything from dried fish to basketball-sized Pomelo (a citrus fruit, locally known as Jeruk Bali).

In Batu Kabobong or “Erotic Mountain”, (named after the ‘use-your-imagination’ visual-shapes of the topography), we learned one of the seminal Torajan myths. In olden days, people were free to climb the Celestial Ladder to meet the deities in the sky, particularly Puang Matua, the High God. Puang Matua wanted to see the Aluk (‘the way of the ancestors’ or ‘the law’) brought down to earth, and so a man and his wife were assigned to carry all 7777 Aluk down the Celestial Ladder. But the couple could only manage to carry 777 and left the rest behind, including the Aluk on permissible marriage practices.

Many years later, a great-grandchild of the couple had two daughters and two sons. As there were no available partners for the children to marry, the parents sent an emissary to climb the Celestial Ladder and ask Puang Matua if the children would be permitted to marry each other. The emissary decided not to undertake the tiring journey and instead, made up the answer. He informed the parents that siblings were permitted to marry, and the marriage went ahead. Puang Matua was so enraged that the Celestial Ladder was hurled down to earth. Over the years, the remaining Aluk that would provide direction for all aspects of social life, agricultural practices and rituals, were conveyed to the Torajan people.

On the final leg of our journey we turned inland and after encountering miles of steep, winding roads, we finally arrived at the formal “Gateway” to Tana Toraja in Rantepao, the capital of North Toraja Regency. We settled into our hotel, enjoyed a local dinner of Nasi Goreng (fried rice with vegetables, shrimp and egg), and then fell asleep to the harmonies of chirping cicadas and crickets.

The next three days were filled with one fascinating experience after another.

Torajan funeral ceremonies allow the soul of the deceased to be transported safely to the next world. As it can be a very elaborate and expensive ‘production’, ceremonies often take years to plan. Hundreds of guests arrive and walk around the ritual field in the village, showing off their best attire as well as the number of pigs they have brought, or baskets of rice or tubes of palm wine. Each gift represents a debt and a social tie. The guests then retire to temporary shelters, built around the field.

Water Buffalo play an important role in leading the deceased to the afterlife. After the Buffalo are paraded on the field, they are slaughtered and the meat is divvied up according to the rank of the attendees (the head goes to the highest noble, the ribs are distributed to commoners etc).

And while this is taking place it’s hard not to notice the Tongkonan (meaning “sit down together”). Tongkonen honour the birthplace of the parents, grand-parents and ancestors, and are characterized by roofs that resemble boats. While some say that this tradition commemorates the ancestors who sought shelter by turning their boats into houses, others believe that the roofs resemble the shape of the sky and are a connection to Puang Matua.

Tongkonen are often elaborately decorated with colorful symbols: Two roosters signify the rule of life; a circle represents Puang Matua; snail-like decorations relate to community and the ideal of working together; and the Water Buffalo represents power. In fact the most important Tongkanen display a ‘kobongo’ on the façade; a carved buffalo head with real horns, often accompanied by a roof-to-ground display of buffalo horns, symbolizing the age, wisdom and stature of the man of the house.

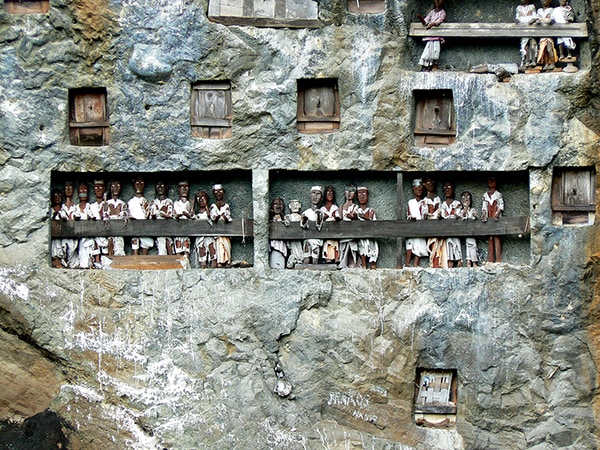

During the time it takes to arrange a funeral ceremony, it’s not unusual for the body of the deceased to remain embalmed, under a house. Afterward the deceased may be formally buried in a cliff grave (inside the cliff or in a wooden coffin hanging from the cliff) or in a cave. We visited some of these gravesites but also saw tree graves where young babies are laid to rest. The belief is that the baby will be absorbed into the tree and the wind will take their soul to the heavens.

Probably the most notable symbols associated with death in Tana Toraja are the Tau tau, a name that means “person-like”. These life-sized wooden or bamboo effigies that guard the nearby graves, are thought to be receptacles for the ghosts of the deceased. Tau tau appear to be alive, with vivid staring eyes and dressed in the finest clothes, while standing or sitting in family groups, in recesses carved into the limestone cliffs and inside caves.

Our visits to explore these important life-cycle events took us to small settlements in Lemo, Sangalla, Marante, Londa Kete, Keta Kesu and Pangli. But we also had the opportunity to trek from one farming village to another, to visit and chat with locals working in rice terraces, tending crops, and engaged in household chores.

In Rantepao and Makale, we visited the lively, crowded markets, watched the animated trading of palm-leaf-and-bamboo-bound live pigs and frantic, squawking chickens, drank fresh coffee brewed from locally grown beans, sipped palm wine from bamboo tubes, and took photos of the colorful fruit, fish and vegetable stands.

This was one amazing adventure filled with memorable conversations and smiles. For travelers with a consuming curiosity about destinations, people and culture, a visit to Tana Toraja can be a defining experience.

www.indonesia.travel