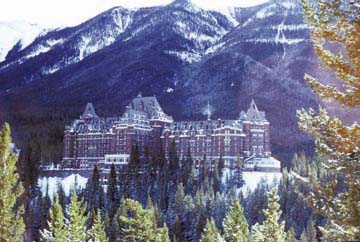

Banff National Park

Wild Worlds: Banff, Alberta in Winter

By Dave Taylor

Published in the January-February 2005 Issue of Canadian World Traveller

Photos: Dave Taylor (www.davetaylor.ca)

There are many reasons to visit Canada’s renowned Banff National Park in winter. Some come to ski the alpine slopes, others choose to ski cross-country through the valleys. Some come to enjoy the skating at Lake Louise while others just come to enjoy the snow-covered scenery. For me a winter visit to Banff provides an opportunity to enjoy watching wildlife.

Winter is a natural bottleneck for wildlife. The term “bottleneck” is one used by ecologists to describe a period of the year when things are tough on animals (and plants too for that matter). Many animals enter the winter months but not all of them are around to enjoy spring Greenup.

There are several factors at work here that determine which shall live and which shall perish. Winter conditions are obviously one determining factor. It is, as every Canadian knows, not the cold but the “wind chill factor” that make life tough here. Canadian wildlife can withstand cold temperatures. It is the wind that they need to fear. The wind chill factor is a measure of the effect of the wind on exposed flesh.

Want to see how this works? Lick your finger and blow on it. Your finger feels cooler where your breath blows over the moisture. But do you know why this is so? It is because on the surface of the skin there are tiny molecules. Some are warmer than others and the warmer ones have more energy and are less tightly bound to the skin. A bit of wind carries them (and their heat) away. The result: your finger feels cool. (We use the same trick to cool down hot soup.)

For Banff’s bighorn sheep or elk the wind is a deadly enemy and can rob the animal of much needed body heat. The condition the animal enters winter is another factor.

A healthy fat animal with a good coat is well protected from the wind but a weak or under nourished animal has little defense.

There is some natural protection from the wind chill even though it seems at first to be a paradox. Animals will seek colder air to keep warm. The colder air is under pine or spruce trees where the sun’s rays don’t reach. Here in the shade it is cooler but the trees’ needles and boughs prevent the wind from robbing the animals of heat. So when you look for animals in winter look where the conifers are found.

The amount of food available is another “bottleneck” factor. By the time the first snow falls there is no more food being created. New growth won’t return until spring and so the animals must make do with what the growing season produced. When that food is gone it is gone. Some species avoid this problem by simply leaving the area for warmer climes where food is still being produced. Birds can migrate, larger mammals cannot.

Mammals are limited in their options. Some like bears, groundsquirrels and marmots simply sleep through the winter. A small rabbit-like animal, the pika, stores grasses and other green plants and literally makes hay to see it through the winter.

But as anyone who has been to Banff in the winter knows there are plenty of big mammals around to see. Elk and mule deer seek the grassy meadows (and even the lawns) around the town site. Wind can be helpful as well as deadly and where the wind sweeps away the snow the grass is easy to get to. Bighorn sheep take advantage of wind blown slopes too. All these species also slow down their metabolism as well in order to require less food.

Large predators go where their food is. Cougars, wolves and coyotes are present (although with the exception of coyotes they are rarely seen). These hunters and scavengers know that winter will weaken or kill some of the hooved animals and they are there to take advantage of the opportunities presented.

Ravens and bald eagles are also common at this time of year. Both are scavengers and where a carcass exists they will find it. Sometimes they even beat the wolves to it.

Even if an animal enters the bottleneck season fit and alert it still has no guarantee that it will survive. Luck (or chance) also plays a part. Deep snow may slow down its escape from predators. A sudden avalanche may catch it unawares. It may just have the bad luck to walk under a ledge where a cougar lies in ambush. The ice may break as it crosses a frozen river.

Age too is a factor. Old animals may simply run out of time and young of the year may lack experience or not be big enough to survive.

For an ecotourist in Banff all this drama is played out each day in the park. The longer your visit, the more of it you will witness. But it is not all doom and gloom there is much that is beautiful and at times even mildly amusing.

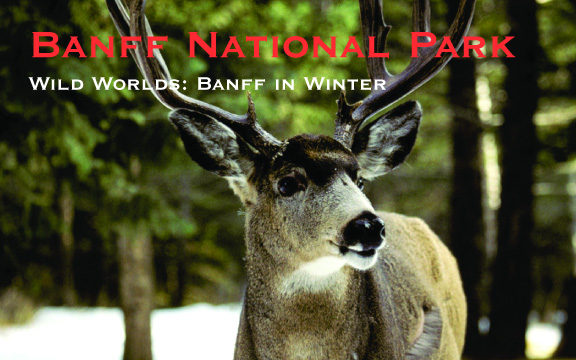

In early winter the deer family are looking their best. The elk and moose have both passed through their breeding season (September into October) but still sport their breeding coats and in the case of the males their magnificent antlers.

Antlers are designed as aids in obtaining a mate and are rarely used to fight off predators. The bigger an antler, the more successful a male will be at finding a mate. Think of antlers as big showy cars. They are a bull elk’s way of advertising to a cow that he is a healthy successful individual skilled at being a survivor. Size matters. Females will accept as a mate the bigger showier bulls over a small bull. Bigger antlers intimidate smaller bulls.

By the end of January the moose and mule deer have lost their antlers. Mule deer rut later than do their larger relatives. Their breeding season is in November and December but soon drop their antlers when the excitement is over. Elk bulls retain their antlers well into March. One wonders why this should be as the antlers are large and heavy. There is a cost to keeping them. They use up precious energy carrying all of that weight around. But perhaps there is a benefit too. Elk, more so than mule deer and moose, are herd animals and by keeping their antlers they may be able to chase off rival elk from the better feeding spots.

Bighorn sheep, often seen on the highway seeking road salt, never loose their horns. In December the males seek out the ewes and their rut (mating) season begins. They will often stay with the females well into the winter before heading up into the high country where they will feed and rest as they prepare for next year’s battles. The bigger the horns the older the ram.

For males the fall and early winter breeding season is the biggest bottleneck of all. The biggest males may spend so much time chasing, defending and herding females that they fail to eat enough to replenish lost energy. Bruised, underfed and tired they may be truly unprepared for the rigors of winter.

The next time you visit the mountain parks to ski take sometime to observe the wildlife. There is much more going on than you might at first think.

I must add a word of caution. These are wild animals and an elk or a moose can do great damage to you. If you are tempted to approach one on foot take care. I’ve seen them charge people who think that these animals can be petted. Hoofed animals in national parks seriously injure more people than are ever hurt by bears!

Also take care while driving. I’ve come to believe that large animals that live by the road learn to avoid traffic moving at posted speed limits. They are ill prepared to avoid speeders. Use extra caution at night.

About the Author

Dave Taylor is the author of over thirty books and numerous articles about wildlife, ecology and ecotourism. He also works as a freelance nature photographer and his work has appeared in numerous books, magazines and calendars. He can be reached through his website: www.davetaylor.ca

For More Info:

For more information about Banff National Park in winter visit the following websites:

http://www.canadianrockies.net/

http://www.pc.gc.ca/pn-np/ab/banff/index_e.asp