Guyana

A Visit to Guyana’s Kaeiteur Falls

Article and photography by Doreen Hemlock

We heard the rush of the massive waterfall before we saw it. We were walking down a rainforest path in a remote national park, just a small group of visitors with two local guides, snaking between towering trees and occasional luminous blue butterflies the size of my hand.

My heart was pounding. My Guyanese friend Wesley had told me about Kaieteur, often called the world’s largest single-drop waterfall. Its broad waters plunge off a ledge straight down without hitting another spot along the way, falling 741 feet in one swoop – or roughly the height of a 74-story building. That’s four times taller than Niagara Falls on the US-Canada border. Yet Kaieteur receives only about 8,000 visitors per year, compared to over 7 million at Niagara. I was thrilled to be so near.

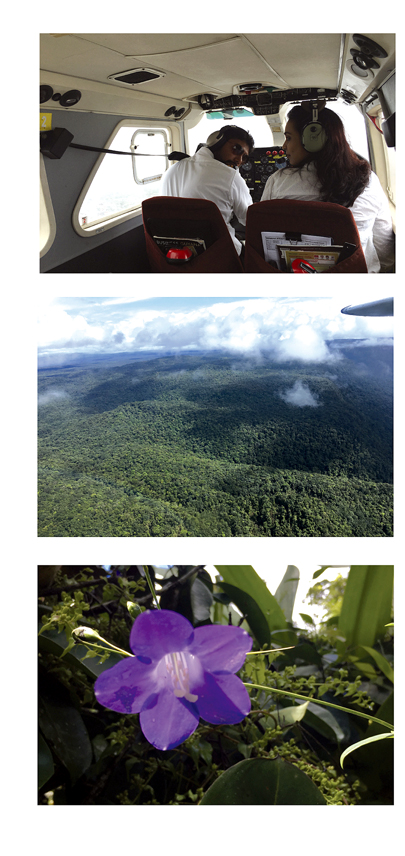

Wesley and I had set out from the capital of this former British colony in South America early morning to board a 17-passenger plane. The pilot flew 11 of us more than an hour over miles and miles of greenery – first plains, then hills and highlands. The virgin forests below looked like broccoli plantations, the tops tufted like florets. Sinewy ribbons of chocolate-colored rivers sometimes peeked through the trees.

From the air, we glimpsed some small waterfalls, but suddenly, as if out of nowhere, emerged Kaieteur, gushing down golden-brown, enormous. The nearly black Potaro River spilled over a wide cliff, and the water dropped into a gorge, mists rising and rainbows too. I gasped, elated.

We circled with the plane, but Kaieteur retreated into the tropical forest. I was eager to see it without light reflecting off the plane window and without the hum of propellers drowning out nature’s music.

Within minutes, we landed on a dirt airstrip, the only plane in sight. Just off the runway was a small wooden building with a sign for Kaeiteur National Park. We meandered over to meet our guides, Candace Evans and Lincoln Pereira, both in their 20s and from indigenous communities nearby.

Candace instructed us to stay on the trails, and at lookout points, to keep at least eight feet away from the edge of the rocky slabs above the gorge hundreds of feet below us. Kaieteur has no safety rails, aiming to remain as pristine as possible. “Please don’t try to prove yourself,” she requested.

We’d walked only a few minutes when Candace pointed out something I’d never seen: “carnivorous” plants. The reddish groundcover secretes a substance that attracts mosquitos and other bugs. “When the insects come, they stick on, and the plant eats them. So, we don’t use mosquito repellent here but have it naturally,” she joked.

Soon, after navigating steps and rocky paths, I heard it: the rush of Kaieteur, a strong and constant whir, not threatening but somehow life-affirming, almost meditative. We followed the sound. At the first lookout, I saw the caramel waters pour over the ample ledge. Two furrows crossed into a white-capped “V” near the top, reminding me of a heart, perhaps the heart of Mother Nature herself.

Our guides told us the dark color of the water came from tannins in the roots of the trees by the river, a tributary of the Essequibo and part of the greater Amazon basin.

The name, Kaieteur, may well come from legend, Candace explained. The story goes there was an old man, or Kaie in the Patamona language. He was chief of a tribe engaged in a bitter war with the Carib tribe. The chief threw himself over the falls, or Teur, in an act of self-sacrifice to stop the war. “Don’t repeat yourself, and say Kaieteur Falls,” or Old-Man-Falls Falls, she advised. “Say Kai Falls or Kaieteur.”

In all, we spent about two hours near Kaieteur, stopping at three lookouts, the closest one to the water called “Rainbow View” for the swirls of light that appear in its mists. Our timing was good: In late spring and summer, the river hits its peak flow, expanding to cover more of the rocky ledge. The waters widen up to some 390 feet – a distance longer than a soccer or U.S. football field, bigger than I’d imagined.

The trails proved a revelation too. Candace showed us the woody vines named “cufa,” used to make furniture, and “capadula,” boiled to make an aphrodisiac dubbed the local Viagra. We saw flowers blooming in purple, pink and white and others jutting out spiky red. My heart was full.

Others in our group felt similar joy, as we headed back to the airstrip. “I was telling my son: The flight alone was worth it for the view from overhead,” said Shanta Lall, 57, a homemaker from Guyana on her first visit to Kaieteur. “This is a bonus,” she said, after gazing at the falls head-on, the air moist and fresh.

We stopped at the national park center for water and snacks, chatting contentedly, before flying out. A small exhibit identified the hand-size butterflies I’d seen as iridescent Blue Morphos, South America’s largest. We also learned that Angel Falls – located just west in neighboring Venezuela – is taller but thinner than Kaieteur, sending far less water in its gorge and producing a less powerful sound.

Wesley was relaxed, proud to share his country’s top natural attraction with me. “Coming here,” he said, “you can forget what day of the week it is, what time of the day it is.”

On the flight back, we circled Kaieteur again as if to bid farewell, then descended from the highlands to the plains and the city. The excursion took only a morning but created a memory for a lifetime.

Click on cover to view published article