USA

Kitsch and Kicks on Arizona Route 66

Article and photography by Randy Mink

Before being bypassed by an interstate highway decades ago, Route 66 was the chief thoroughfare in Northern Arizona for more than 50 years. Dubbed “Main Street of America,” the storied asphalt artery traversed thriving towns lined with roadside curiosities, friendly filling stations, and mom-and-pop motels and diners.

Many communities along the 2,448-mile diagonal corridor from Chicago to California have been reduced to backwaters, but that just adds to their charm. Happily for nostalgia-minded tourists, some towns cling to their Route 66 heritage, and this passion for the past will be on full display in 2026, when the road celebrates its 100th anniversary.

Today the two-lane ribbon of roadway—a true slice of Americana—has become a destination in itself, a romanticized symbol of simpler times that captivates travelers from around the world. Many original stretches, signposted as Old or Historic Route 66, still exist across the land, offering a look at the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s and ’60s through the rear view mirror.

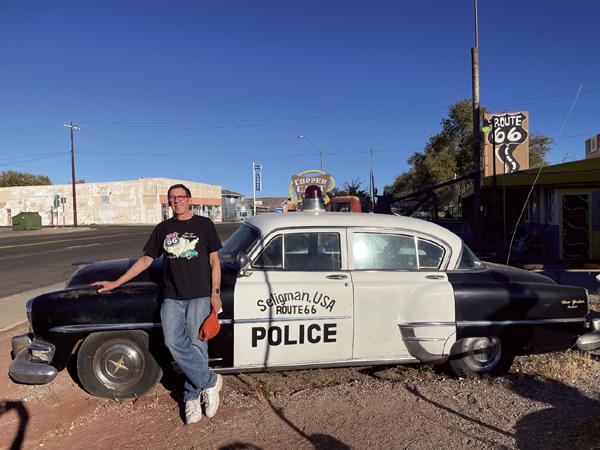

A big Route 66 fan and collector of vintage signs and Coca-Cola memorabilia, I recently spent four magical days soaking up retro vibes on a bucket-list driving trip with my son. Traveling from Las Vegas, we covered the western and central portions of Arizona Route 66, starting in Kingman.

Each town we visited seemed to be more special than the one before. With my iPhone camera I went wild clicking away at neon signs, gas pumps and rusted cars of yesteryear prominently displayed at stores and museums, motels and restaurants. I couldn’t get enough of these relics from the heyday of automobile travel.

Arizona takes pride in being the first state to form an association dedicated to preserving Route 66’s heritage, and the Seligman-Kingman stretch was the first in the country to be designated as Historic Route 66.

Kingman, Oatman and Hackberry

The town of Kingman, conveniently situated on Interstate 40, made a good starting point for us, as it is home to the Arizona Route 66 Museum. Housed in the city’s former power plant along with the Kingman Visitor Center, the museum chronicles the area’s pioneer past and the road’s history as a pathway for both tourists and folks seeking a better life out West. I liked the poignant exhibits depicting refugees from the Dust Bowl that ravaged mid-America during the Great Depression, their westbound trucks piled with furniture. In his 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, author John Steinbeck called Route 66 the “road of flight” for destitute families fleeing from drought and economic hardship. He coined the term “Mother Road,” a moniker used today.

The museum’s diner, gas station and barber shop mock-ups invite selfies, as does a lovingly restored 1950 Studebaker Champion. But the best photo op may be in the parking lot, where you can park your car inside the arch forming the giant Route 66 Drive-Through Shield.

Mother Road fans in Kingman also seek out Mr. D’z Route 66 Diner. Whimsically painted teal and pink, it serves up house-made root beer and comforting classics like chicken-fried steak, burgers, shakes and sundaes, all to the tunes of golden oldies.

After Kingman, our first big adventure was the 50-minute drive to the old gold mining town of Oatman, 30 miles to the southwest. On the way, we stopped at Cool Springs Gift Shop & Museum, built in the early 2000s on the remains of a 1920s gas station/tourist camp. Then we drove nine more miles to Oatman, and what a nine miles it was! It’s hard to believe this twisty road through the Black Mountains—full of switchbacks and sheer drop-offs—was part of a major thoroughfare, Route 66.

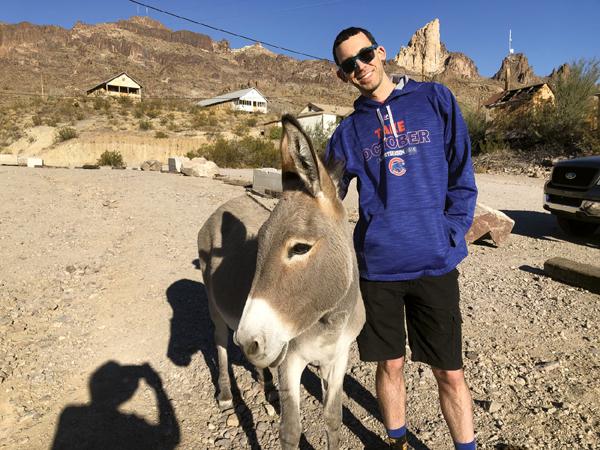

Like every tourist in the tiny town of weathered wooden buildings and plank sidewalks, we made friends with Oatman’s free-roaming resident burros, descendants of pack animals that hauled ore from the mines. Visitors have a field day posing with the docile burros that seek handouts of hay cubes sold in the stores.

The Oatman Hotel is where movie stars Clark Gable and Carole Lombard spent their honeymoon in 1939. Now a free museum that allows a view of their room, the two-story adobe building has a bar/restaurant papered with $1 bills.

The best concentration of photo opportunities on Arizona Route 66 awaits at Hackberry General Store, a half hour from Kingman. The grounds are strewn with old cars, antique gas pumps and rare signs. Inside the ramshackle building, a major service stop from 1934 until the 1970s, you’ll find license plates plastered on the ceiling and a soda fountain set-up with Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. Offering every imaginable type of Route 66 curio, the store has been called the “mother lode of Mother Road memorabilia.”

Cruising on to Seligman and Williams

If I had to choose one town to savor and explore, it would Seligman, population 700. Called the “Birthplace of Historic Route 66,” it is practically a pilgrimage site for Mother Road aficionados, as a group of citizens from Seligman and other communities, led by barber shop owner Angel Delgadillo, in 1987 started the movement to revive Route 66 and breathe life back into dying towns. The group’s efforts to rally business owners ultimately resulted in Route 66 being designated a historic highway, inspiring similar efforts in other states.

The barber shop, opened along with a pool hall in 1950, is now a shrine where you can sit in the swivel chair and stand with a color photo cut-out of Angel. Adjacent, Angel and Vilma’s Original Route 66 Gift Shop, managed by their daughters, operates out of the former pool hall.

Now 97 and retired, Angel has received worldwide fame for saving a piece of American history. Pixar director John Lasseter’s interview with Angel helped shape the storyline of the 2006 computer-animated movie Cars.

Another Seligman must-see is Delgadillo’s Snow Cap, a drive-up eatery established in 1953 by Angel’s late brother, Juan, and now run by his children. On the patio, I enjoyed the best-ever peanut butter banana malt. The menu lists everything from burritos to snow cones. Cluttering the restaurant’s backyard are aging vehicles painted with googly-eyed windshields, a nod to Pixar’s Cars. We stayed across the street at the Aztec Motel, which opened in 2023 in a building that has housed many businesses over the years.

One night we dined at Roadkill 66 Cafe, whose motto is “you kill it, we grill it.” None of the dishes served have really been scraped off the road, but the creative titles on the menu are a hoot. Randomly named, items include Curbside Kitty, Buzzard Bait, Vulture Vittles, Roadside Revenge, Treads & Bread, Armadillo on the Half Shell and Too-Slow Doe. I had the BBQ beef sandwich and a big slice of lemon meringue pie.

Like Seligman, the town of Williams (pop. 3,000) worked its magic on us, delivering a solid dose of nostalgia in the six-block stretch of historic downtown. Neon lights, souvenir shops, retro diners, classic cars and old-school motels make it a Disneyland for Route 66 fans.

We stayed at The Lodge on Route 66, a motor court where each room is named after a town on Route 66. Blocks away were places like Pete’s Gas Station, a Route 66 museum/gift shop, and Cruiser’s Cafe 66, a 1930s filling station turned diner whose patio tables are set among restored gas pumps and Coca-Cola artifacts.

Our four-day Route 66 odyssey was packed with adventures from morning to night, but we only scratched the surface and yearn to return. Next time we’ll concentrate on the section from Flagstaff to the New Mexico border—for another epic road trip.