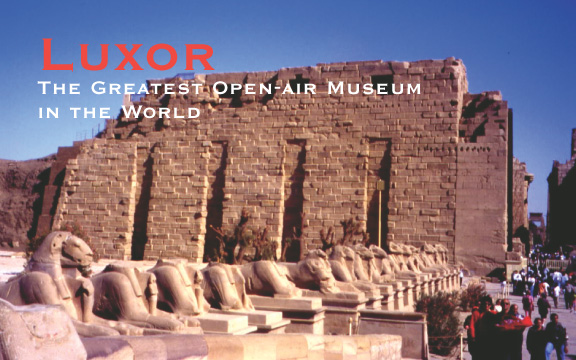

Luxor

The Greatest Open-Air Museum in the World

By Habeeb Salloum (habeeb.salloum@sympatico.ca)

Published in the October, 2004 Issue of Canadian World Traveller

Photos Courtesy of Egyptian Tourism Office www.egypttourism.org

What impressed me most in Egypt were the pharaonic monuments. Today’s Egyptians still live off the remains of their ancestors. This was the remark made by a Canadian friend when I asked her about the tour she had just made to that ancient land.

Now, after I had ended my exploration of Luxor’s awe-inspiring conglomeration of monuments, I remembered her words. In this greatest open air museum on earth, one can truly appreciate the Ancient Egyptians’ contribution to world civilization. There is no place else on earth where so many ruins are concentrated in this one spot – once named Weset, later changed to Thebes by the Ancient Egyptians.

Homer in his Iliad described Thebes, capital of the Egyptian Empire for a thousand years, as ‘the hundred-gate city for which only the grains of sand surpassed the abundance of wealth contained therein’. When the Arabs came in the 7th century A.D., they saw Thebes’ mass of huge structures and named it Al-Qusoor (the castles) from which we get Luxor – today a city of some 200,000.

Homer in his Iliad described Thebes, capital of the Egyptian Empire for a thousand years, as ‘the hundred-gate city for which only the grains of sand surpassed the abundance of wealth contained therein’. When the Arabs came in the 7th century A.D., they saw Thebes’ mass of huge structures and named it Al-Qusoor (the castles) from which we get Luxor – today a city of some 200,000.

As a testament to their desire for immortality, the Ancient Egyptians were the only people who wrote manuals for the other world. In Luxor and elsewhere, they built for eternity with sandstone and granite. In the spirit of the ever-lasting, their still-standing temples and tombs are a mecca for millions of tourists from the four corners of the globe.

The fear of terrorism, which had kept tourists away for a number of years, has faded as the Egyptian government has gradually taken control of the situation. When I asked Hashim, my driver, bringing me on a desert road from Hurghada, Egypt’s top Red Sea resort, to Luxor, whether terrorism is still a problem, he replied: “al-hamdu-Allah (praise be to God), for a long time we have not had one incident against tourists. Al-hamdu-Allah, Egypt welcomes all visitors.”

Amid the breathtaking splendour of Luxor’s pharaonic monuments where imagination overtakes eyesight, thousands upon thousands of these visitors take a thrilling walk through history. Beneath pillars carved with lotus buds and the papyrus plant, past statues of gods and animals, and climbing down into fantastically decorated tombs, they are never far away from the early Egyptians and their remains.

Pharaonic Thebes, a city of a half million, was divided into two parts: on the East Bank of the Nile, the City of the Living; and on the West Bank, the City of the Dead. The Karnak and Luxor Temples where the gods lived – two of the 10 temples in the area – greet the sunrise on the East Bank; and the sunset on the West Bank throws shadows over the 400 tombs of Queens and Nobles, located in the Valleys of the Kings. The whole site was organized for those alive and for the ones who travelled to the other life.

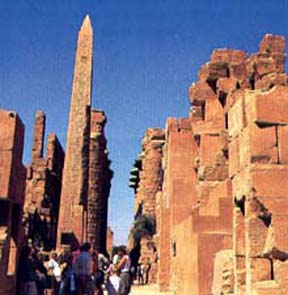

Guides usually begin their tours on the East Bank at the Karnak Temple complex – to the ancient Egyptians, the most esteemed of places. Covering over 40.5 ha (100 acRes) and spanning thirteen centuries, the complex is a massive collection of ruins on which at one time 81,000 people toiled – the largest series of temples ever built in one place. Dedicated to the god Amon-Ra, king of the gods; his consort, Mut; and their son Khonsu, Karnak, is a holy city of colossal statues, hypostyles halls, obelisks, pylons and shrines.

Guides usually begin their tours on the East Bank at the Karnak Temple complex – to the ancient Egyptians, the most esteemed of places. Covering over 40.5 ha (100 acRes) and spanning thirteen centuries, the complex is a massive collection of ruins on which at one time 81,000 people toiled – the largest series of temples ever built in one place. Dedicated to the god Amon-Ra, king of the gods; his consort, Mut; and their son Khonsu, Karnak, is a holy city of colossal statues, hypostyles halls, obelisks, pylons and shrines.

Past the two gigantic statues of Ramses II, who sired 100 daughters and 65 sons and was the only pharaoh who declared himself a god while still living, one enters the pantheon between two huge pylons. Inside, a 300 ton statue of Ramses II, later usurped by King Pinedjem, stands guard at the entrance to the huge hypostyle passageway. The hall’s colossal 134 columns, 23 m (75 ft) high, have capitals in the form of the lotus plant – atop of each can stand 50 people.

Beyond are many other halls and statues, a sacred lake and three grand obelisks, the ones remaining from the seven that once graced this house of the gods – the other four are in Istanbul, London, New York and Rome.

As we walked out of this awe-inspiring pantheon, the words of our guide, Muhiyadeen, had a ring of truth when he remarked, “In my opinion Karnak should have been the first among the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’.”

After a tour of this most massive of ruins on earth, for an unique experience, one should take in the ‘Sound and Light’ show held within the temple. As the visitor moves between the massive columns, voices seemingly from the world of the past relate the history of Thebes. Throughout the presentation, one feels the grandeur of a civilization which in the mist of time created such a structure.

The Luxor Temple, 3 km (2 mi) away from Karnak, was once joined to that pantheon by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes – many of which still remain. However, only a modest section of this passageway has been excavated. The remainder remains under homes and mosques, waiting to be uncovered.

It took 200 years to build the Luxor Temple – a much smaller version of its older twin. In pharaonic times, every year in late August, the marriage of the gods Amon and Mut was celebrated for 15 days. The sacred boat of Amon-Ra, followed by those of Mut and Khonsu, were carried between the sphinxes with music and dancing from his home in Karnak to the Luxor Temple, then returned a few days later, amid much merrymaking.

Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C. expanded the Luxor Temple and later the Christians turned it into a church. By the 12th century, it was a pile of ruins covered by sand. In 1130 A.D., the oldest mosque in Luxor, Abu al-Hajjaj, was built on land covering the top of its lotus capitals. After an adjoining portion of the temple was excavated, the mosque appears to be suspended high above the temple floor.

From the East Bank, we crossed the Nile to the City of the Dead where our guide had planned for us visits to a number of pharaonic tombs and temples. The most important site in this barren burial spot is the ‘Valley of the Kings’ – the necropolis of the great Egyptian sovereigns where some 64 of Egypt’s pharaohs had their palatial resting places hewed into the sheer rock.

From the East Bank, we crossed the Nile to the City of the Dead where our guide had planned for us visits to a number of pharaonic tombs and temples. The most important site in this barren burial spot is the ‘Valley of the Kings’ – the necropolis of the great Egyptian sovereigns where some 64 of Egypt’s pharaohs had their palatial resting places hewed into the sheer rock.

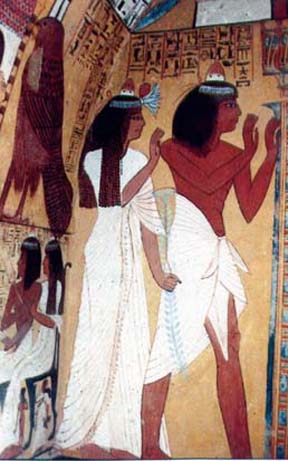

Here, the first vault we visited was that of Ramses 1V, the largest in the entire Valley and once used as a Christian church. Among other magnificent decorations, the tomb features scenes from the ‘Book of the Dead’, ‘Book of the Gates’ and ‘Book of Caves’.

A short distance away, we stopped at the famous Tomb of Tutankhamen – the only grave discovered with all its treasures. It was uncovered in November 1922 by the Englishmen Lord Carnarvan and Howard Carter. Today, his small tomb is empty except for the sarcophagus and the deteriorated mummy. Its 4,000 piece rich contents are exhibited in the Egyptian Museum of Antiquity in Cairo.

From the grave of this boy-king, we explored the Tomb of Ramses III, a warrior king who defeated a coalition of ‘sea nations’ and Libyans. Noted for the frescos in its walls depicting life in ancient Egypt from the playing of music to the use of perfumes, it is a very impressive burial chamber.

After visiting the Tomb of Ramses I – the best preserved in the Valley of the Kings – we left for the Valley of the Queens. Here, we stopped at the Temple of Hatshepsut or Deir al-Bahari (Convent of the North) built by Queen Hatshepsut 1501 -1481 B.C.), the most renowned of all the Ancient Egyptian queens and the only woman to govern Egypt as a pharaoh. She ruled the country for 20 years and built the sanctuary in honour of her father, Thothmes, and herself. Consecrated to the goddess Hathor, she called it ‘Splendour of Splendours’. Later, it was converted into a Christian convent and thanks to this, the Temple has been well-preserved.

Leaving this imposing shrine, carved into a stone mountain side, we drove to the Colossi of Memnon. These two huge statues, the only remains of the Temple of Amenophis III, became a legend in Greek mythology.

At these deteriorating statues where pharaonic and Greek gods became intermixed, we ended our tour of the City of the Dead – the most important necropolis in human history. It is a spot that has kept alive for thousands of years the history of the pharaohs and their amazing achievements – a place that should be a must on any visitor’s itinerary.

The optimal time to travel to Pharaonic Thebes and its necropolis is in November. Annually, on the 21st of this month, for four days, a national celebration, featuring dancing, music and acrobatic feats, is held in honour of King Tutankhamen.

The optimal time to travel to Pharaonic Thebes and its necropolis is in November. Annually, on the 21st of this month, for four days, a national celebration, featuring dancing, music and acrobatic feats, is held in honour of King Tutankhamen.

During this fun-filled period, a visitor can live for a time in the era of the fabulous pharaohs who created ‘the mother of all civilizations’.

About the Author

Habeeb Salloum is a freelance writer, author and member of Travel Media Association of Canada (TMAC). He has travelled extensively to most parts of the world and has written comprehensively about topical items, tourism and the cuisines of the countries through which he has journeyed. Many of his writings can be found on the internet.

For More Info:

Egyptian Tourist Authority in Canada

2020 University, Suite 2260

Montréal, QC H3A 2A5

Tel.: 514-861-4200

Fax: 514-861-8071

Email: info.ca@egypt.travel

Official Website: www.egypt.travel

Embassy of Egypt

454 Laurier Avenue East

Ottawa, ON K1N 6R3

Tel.: 613-234-4931 Fax: 613-234-9347

Email: egyptemb@sympatico.ca

Official Website: www.egyptembassy.ca

Egyptair

630, boul René-Lévesque O, Bureau 2860

Montréal, QC H3B 1S6

Tel.: (514) 875-9990

Email: egyptair@egyptair.ca

www.egyptair.ca