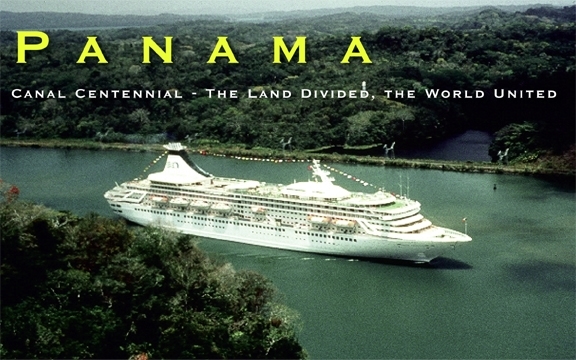

Panama

Canal Centennial – The Land Divided, the World United

Article & Images by: Alan G. Luke

In 1903, a treaty between the newly independent Panama and the United States permitted the U.S. to undertake the construction of an inter-oceanic ship canal across the Isthmus of Panama.

“Undertaking” was the operative word since 500 lives were lost for every mile of the canal constructed, more by disease than accidents. President Theodore Roosevelt stated during his initial Congressional address: “No single great material work which remains to be undertaken on this continent is of such consequence to the American people as the Panama Canal”.

Since the end of the century, the control of the canal has reverted to the small Central American country, truly marking the end of an era. This reluctant relinquishment by the United States may have resulted in “separation anxiety”. However, minimal change has occurred, state most cruise lines. When changes actually materialize, they will quite likely benefit cruise patrons. New excursions will provide passengers with a relatively extensive ecological experience similar to that of Costa Rica but sans wildlife. During this phase, plans have been made for beach hotels and even golf courses. Evidently, some of the property under consideration is that of former U.S. military bases. Prior to the American venture, the French effort (1882-89) on La Grande Tranchie (The Great Trench) was brought to bankruptcy and disgrace due to disease and financial problems.

Although the premier promoter, Ferdinand de Lesseps, was the chief engineer of the Suez Canal, this constructive creation would not reach fruition. Eventually, it evolved into a sophisticated engineering feat that was a veritable convergence of men, might and money which made this modern marvel a magnificent monument that defined a defiant era. It was also the first time electricity was utilized on such a massive scale. The “Big Ditch” provided a vital international trade link when it officially opened on August 15, 1914. Although it was overshadowed by the start of World War I, less than two weeks before, the impressive entity trims over 8,200 miles (13,120 km) off the New York City – San Francisco route.

It generally requires 9 hours for the average ship to traverse all 3 sets of locks (Gatun, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores) along the 48-mile (77 km) waterway. All locks weigh 730 tons each and it takes over 26 million gallons (100 million litres) of water to raise a ship in them. Currently, more than 14,000 ships, including over 250 cruise ships, gain annual passage through the canal system paying tolls based on gross tonnage. Several of these offer a partial transit, entering and exiting from the Caribbean Sea.

The Canal Visitors Center & Museum is an impressive facility located on the east side of the Miraflores Locks. It features observation terraces, a theater, a restaurant and a hall of special events. Video presentations and interactive modules can be experienced within the four exhibition halls. “Beyond the Panama Canal” events will unfold throughout the (2014) centennial year.

For those interested in a marginal sampling of this wondrous waterway, a partial tour on a cruise ship is also an inviting venture. Just over an hour later and the vessel has passed through the Gatun Locks and into Gatun Lake after being raised or lowered 85 feet (26 metres) in three stages. Ships are gradually raised above sea level to cross the continental divide. The lake is almost half the length of the entire canal and was the largest man-made lake of its time 24 miles (38 km long).

One can experience the luxuriant security from the upper decks as you scan the 100-foot ferns amidst the mangrove swamp and the massive swath of land wrenched from nature. Some of the “islands” you pass are in reality mountain tops. Viewing the jungle landscape, you can envision this prodigious project being progressively perpetrated as you are transported along this tremendous tropical trough. This man-made miracle of machinery is an accomplishment not to be taken for granted.

Six 55-ton electric locomotives, known as “mules”, guide the vessels into the locks with cables. Each of the 6 double-sided locks has seven foot thick gates with a length of 3 regulation football fields and a volume to accommodate 500 school buses. The individual chambers have the capacity to park four space shuttles and the height is equal to that of the Eiffel Tower. Onboard, a continuous commentary provides you with intriguing information en route.

The successful completion of the U.S. effort cost almost 6,000 lives and $387 million to construct over a ten year period, compared to the aborted French operation that cost 22,000 lives and $300 million dollars over eight years. Richard Halliburton did actually swim the locks in 1928 paying .36¢; today, the mega-liners can pay in excess of $90,000 for a transit fee (with an average cost being $34,000 US).

In 1992, further excavation was initiated to widen the canal which was originally built to accommodate the size of the HMS Titanic that was 46,328 gross tons and carried 2,223 passengers and crew. Generally, the canal cannot accommodate vessels that exceed the 100,000 tons limit depending on their width and length. Numerous mega-ships build over the past several years would get wedged in the “Big Ditch”.

Presently, the world’s largest cruise ship is Royal Caribbean International’s Oasis (and her sister ship Allure) of the Seas at 225,000 gross tons (with a 6,300 capacity). Such behemoths are too large to transit the Panama Canal system. Some cruise lines have been adhering to the “panamax” specifications to ensure their ships are of the nominal size to gain entry into the locks. The introduction of a Panama Canal expansion proposal will build a new lane of traffic along the canal that would double the capacity and allow more traffic. The project is estimated to cost 5.25 billion and would be paid entirely by users of the canal through a graduated system of toll increases.

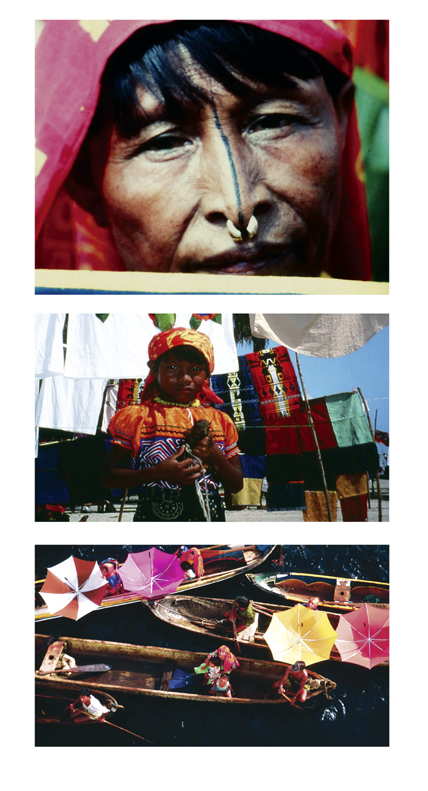

Just off the South American coast, several cruise ships provide excursions to the San Blas Islands. Discovered in 1501 by Rodrigo de Bastidas, the islands became a popular rendezvous point for pirates and privateers alike into the 1700s. Home to native Panamanian citizens, the autonomous Cuna Indians uphold their ancient traditions here. The populace has a restrictive gene pool due to inbreeding and consequently there exists a high ratio of albinism (1 in 220 are albinos). They are monogamous and matrilineal-oriented with a low life expectancy and a high infant mortality rate.

Cruise ships provide tenders to the palm-laden isles where a sun-baked beach barbecue is prepared for the passengers by convivial crew members. Before disembarking for your island tour, the ship is besieged by dozens of dugout canoes. Chanting “money, money” the Cuna Indians dauntlessly dive for quarters thrown overboard or catch the coins in their attractive upturned umbrellas. This colorful and congenial cluster of Cunas encompasses all ages.

Following your beach picnic and excursion on Porvenir Island, a “cayuko” (motorized dugout canoe) tour is available for insight into the indigenous environs. Each canoe accommodates a handful of passengers and travels past a radar installation tower manned by the US military during World War II. Further along you pass by the native cemetery where the deceased are interred in hammocks underground that are sealed but not filled in. Arriving at Nalunega Island (Home of the Red Snapper), one can converse and visit with the Cunas who domicile here in their modest thatched huts.

There are photo opportunities aplenty as you peruse the innumerable molas (reverse appliqué embroidery) on display. These vividly colored, hand-stitched fabrics created by the locals are readily available for purchase at only a few of the islets in the 365-island archipelago.

I realized that this enlightening native and canal encounter reinforced the tangible manifestation of the regional slogan: “The Land Divided, the World United”.