Watching Wildlife in

Madagascar

by Adam Scott Kennedy

In 2013, my wife Vicki and I were fortunate to lead a dedicated wildlife holiday to the Indian Ocean ‘island’ of Madagascar. A year later, I am still unsure how I feel about the country that I had dreamed of visiting since reading Gerald Durrell’s “The Aye-Aye and I” as a child. It is a place of enormous contrasts, the gravity of which I’ll endeavour to encapsulate here.

Perhaps I should first explain the use of parentheses over the word ‘island’? Although it is typically referred to as an African island, the landmass is absolutely huge and many, academics and laymen alike, argue that it should in fact be classed as a continent, certainly from geological and ecological perspectives at the very least. During her university studies, Vicki had spent an entire year on the island, working as a volunteer on various environmental projects and, until my own visit, I had always been surprised at how little of the island she had seen during her twelve months there but now I know why. It takes forever to get anywhere, not least to the island/ continent itself!

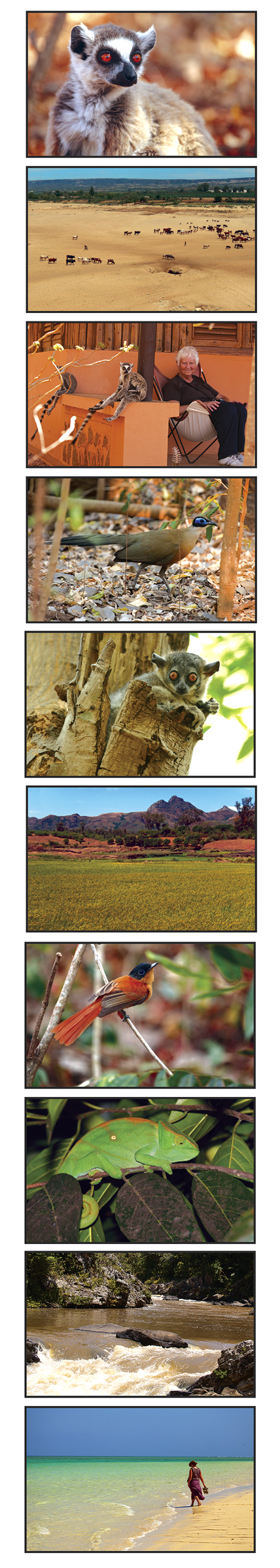

We were there for the wildlife and we did indeed encounter some truly spectacular creatures in some amazing places. Where good habitat remains, the experience is akin to walking within a very large zoo enclosure as you know the target species is ‘in there somewhere’ and that you just have to look. The experienced local guides know their stuff and rarely fail to deliver on your expectations. On the top of most naturalists’ lists are the lemurs and in some places these are easy to find, watch and enjoy. Over 100 species of these primates are now recognised and they vary in size from the tiny Mouse Lemurs (30g of cuteness fitting perfectly in the palm of your hand) to the solid-looking Indri which weighs in at a hefty 9kg.

The diversity is a reflection of the different habitats that exist on Madagascar, from lush tropical rainforests to dry spiny forests and Baobab-dotted deserts. We encountered 23 species on our visit and our favourite was the Verreaux’s Sifaka, seen jump-dancing at Berenty.

The birdlife is equally remarkable. Although we encountered 190 species over the course of 25 days (I’m more used to seeing that total in a single day in Kenya!), the proportion of endemic species is very high and entire bird families occur that are found nowhere else on Earth, such as Vanga, Coua, Asity, Mesite, Ground-Roller and Tetraka.

The reptiles present a really interesting challenge because many are so difficult to observe without help from a local expert. Madagascar is the hub of chameleon diversity and home to the largest and smallest species known to exist, from 15mm Brookesia species (yes that is fully grown!) to the 70cm Parson’s Chameleon, but not even the big ones are easy to find. We observed 24 reptile species, including 9 chameleons, and the highlight was when our guide pointed out a Satanic Leaf-tailed Gecko to the group; it was so amazingly camouflaged that even when the guide put his laser pen on the animal at a range of less than 1m, half of our group could still not make out what they were looking at! Although numerous snakes exist, there are no venomous species on the island.

The following four sites are essential to a visitors’ itinerary and it would be a great shame to omit even one from any wildlife-based tour of Madagascar.

•Perinet-Mantadia

•Ranomafana

•Ankarafantsika

•Berenty

All are home to a fantastic diversity of birds, lemurs and reptiles and offer great opportunities for photography. Coupled with the warmth and friendliness of the Malagasy people, it might be difficult to comprehend at this point how there could possibly be a downside.

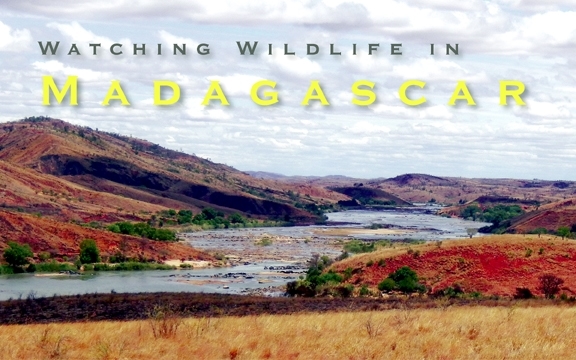

Having travelled to over 35 countries in search of wildlife, I was genuinely shocked and saddened at how little native habitat remains in Madagascar. Commuting from one destination to another, we travelled across the country for many hours, sometimes entire days without seeing so much as lush lake or a community forest where birds could be watched. Vast quantities of the island have been clear-felled of native trees and, typically, all that remains is parched grassland that cannot even support livestock. Poverty, high population growth and unsustainable demand for land and natural resources are not uncommon across the developing world but in Madagascar, the scale is truly staggering. Less visible is the lack of wildlife protection in the few remaining areas where habitat exists and the decimation of lemur populations for the bushmeat trade continues.

Experienced eco-tourists may also be surprised at how wildlife guiding is carried out here. It is far more aggressive than what I have experienced anywhere and on several occasions I was obliged to stop the local guides from ‘chasing down’ very rare birds and lemurs as the experience was troubling most of our party, such was the intensity to deliver the species and to get the tip. The concept of being considerate towards the animal was lost on quite a few of our guides, despite our attempts to educate along the way.

In summary, the truth is that amazing wildlife of Madagascar is amongst the most threatened anywhere in the world and if you’re dreaming of such an adventure, I would strongly advise that you do so sooner rather than later … while flocks last!